Ben Pile The Daily Sceptic 22 January 22, 2025

As needs no retelling here, this week saw the return of Donald Trump to the Whitehouse. Among many of his first acts were important and far-reaching interventions on climate and energy, continuing where he left office in 2020 and re-reversing the changes he made in his last term, which were emphatically unreversed by Biden. So, what were these actions, and what do they mean for the global climate agenda, for Europe, and for Net Zero here in the UK?

In response to what the new President argued was inflation caused by “massive overspending and escalating energy prices”, in his inauguration speech he declared “a national energy emergency”, the solution to which, was: “We will drill, baby, drill.” “America will be a manufacturing nation once again,” he continued, powered by “the largest amount of oil and gas of any country on Earth”. “We will end the Green New Deal and we will revoke the electric vehicle mandate.”

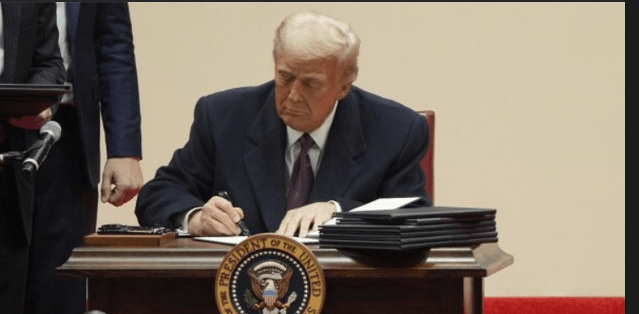

It did not stop there. The inauguration ceremony was followed by an event in which Trump turned authoring Executive Orders into a stadium spectator sport. In front of an energetic, cheering crowd, Trump set alight a bonfire of his predecessor’s interventions. “I’m immediately withdrawing from the unfair, one-sided Paris Climate Accord rip-off,” he told the fans. While Trump held the order declaring America’s withdrawal that he had just signed for their viewing pleasure, the compère explained to the assembly that: “We’re going to save over a trillion dollars by withdrawing from that treaty.”

Some might observe that, no matter which side one takes in American politics and the climate change issue, the handover between Presidents now looks like executive power causing a violent oscillation in policy. Pro-climate Obama was followed by anti-climate Trump, was followed by pro-climate Biden, and now Trump again. This observation may have some merit, and it ought to be remembered that there will be another choice to make in just four short years. But there is very good reason to think that we may be seeing the dying years, if not the days, of the global climate agenda, as well as the terminal point for much of the contents of the agenda that have dominated in the recent political era, to which Trump also laid waste.

The great hope of environmental politics, and latterly the climate agenda, was that it would unite the world’s nations in purpose. Before even global warming and while East and West were locked in the Cold War, the United Nations sought to make green politics global politics and to regulate pollution, resource use and even human fertility. And as the Cold War ended, climate change rose up to dominate the global green political agenda, displacing all the debunked green scare stores of the 1960s, 70s and 80s. But the unipolarity seen in the subsequent decades is now fading, and green politics has neither found the one-size-fits-all global climate policy, nor united as much as divided the world’s increasingly fractured parts.

One characteristic of liberal internationalism, besides its zealous adherence to green dogma, has been its desire to return to Cold War geopolitical geometry. And, as well as being destructive to global security, this contradiction has made it all but impossible for Western dominance of global institutions to bring emerging (and emerged) economies into the green fold. Climate diplomats have practically zero chance of aligning Beijing and Moscow, or New Delhi, Tehran and Rio de Janeiro for that matter, into a lasting alliance. After all, Trump has signalled that the exit from such agreements is as easy as an executive order. And the same signal has been sent by Javier Milei, and is likely to be sent by Pierre Poilievre following Canada’s looming General Election, in a symbolic showdown with arch climate globalist Mark Carney.

This matters, because environmental global politics has been dogged since the outset by the ‘free rider’ problem. China, for example, has been able to capitalise on the idiocy of European climate policy as a free rider, pushing ahead with its own fossil-fuel based economic growth while enthusiastically supporting the West’s self-harming green asceticism. As a master negotiator, Trump is acutely aware of such traps that European (including British) politicians are ideologically blind to. The Paris Agreement was the last gasp of the search for something every government would sign up to. It fudged the issue of a one-size-fits-all commitment by allowing countries to set their own emissions-reduction targets – Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs). The era of climate politics that came after the accord then sought to bypass troublesome democracy by focusing on the ‘plumbing’ of global financial systems – Mark Carney’s expertise.

As has been discussed in recent articles here, Trump’s election win preceded an exodus of financial institutions from the Net Zero alliances that had been forged by Carney in his capacity as UN Special Envoy on Climate Action and Finance. This now includes four major Canadian banks quitting. Though US and Canadian banks made up a relatively small proportion of the total investment in ESG-related funds, which predominantly comes from European banks, the exodus signals a terminal failure to make ‘green finance’ the substance of a global response to climate change.

All of which is to say that, even if Trump’s hypothetical green eventual successor was able to achieve any domestic momentum for global green politics, that agenda will by then have been rendered wholly impotent. The attempt to build global green political institutions above democratic control and to rewire the global economy are already exposed as busted flushes. This is, of course, because there are now major democratic movements alive to the fact that climate policy is far more dangerous than climate change.

At face value, the attempt to solve the world’s problems by building global institutions to tackle them may seem like a good one. Individual states may not be able to respond to seemingly ‘global’ problems that afflict their populations or may be unwilling to act unilaterally to resolve them, both for good and bad reasons. But critics of globalism have long observed that the problems such institutions claim to address are either fictions or better formulated as local problems, and that the international institutions set up to address them are no less self-serving than national institutions.

Consider Ursula von der Leyen’s response to Trump’s moves. On X, the unelected President of the European Commission claimed that, “All continents will have to deal with the growing burden of climate change”, and that, “Its impact is impossible to ignore”. In defence of the Paris Agreement, she claimed that it “continues to be humanity’s best hope”, and promised that the Commission will “keep working with all nations that want to stop global warming”.

The problem for von der Leyen is that the impact of climate change is not “impossible to ignore”, but is impossible to even detect in any metrics of human welfare. At this point, I am usually challenged by X’s green trolls with screenshots of global temperature charts. But greens don’t even understand their own terminology. Climate ‘impacts’ are neither temperature nor even meteorological phenomena but effects on human lives, and greens cannot point to any of those that have been trending in the wrong direction as the planet has gently warmed since the 19th century.

The only way that the proponents of the ‘liberal’ international order are able to process such criticism is to cast it as an expression of manifestly unreasonable character flaws. Ironically, then, angry Eurocrat Guy Verhofstadt took to X to proclaim that “America, as a liberal empire, is no more”, and that the “new era of US governance” is an “oligarchy”, “where billionaire members of Mar-a-Lago decide US policy”. But talk is cheap. Trump is obnoxious to the “liberal” order imagined by Verhofstadt, not because his administration is an “oligarchy”, but because it is a democratic departure from the green oligarchies that dominate in Europe and were installed without due process under the largesse of Green Blob billionaires.

No less an irony, former UK Prime Minister Boris Johnson, who attended the inauguration, claimed to have “witnessed the moment the world’s wokerati had worked so hard to prevent – and a speech that left his opponents chewing the carpet”. As Prime Minister, Johnson had promised to make Britain the “Saudi Arabia of wind” with a “Ten Point Plan for a Green Industrial Revolution” that required banning domestic gas boilers and the sale of petrol and diesel cars.

Much more could be said about Johnson’s agenda as PM, much of which was overturned, in its US form, by other aspects of Trump’s inauguration speech. But this article is about climate change. Following Johnson’s occupation of Number 10, the Government began to wobble. The short-lived Truss administration attempted to lift Johnson’s ban on fracking, leading many to speculate about ‘climate denial’ in Downing Street. But Truss appointed none other than the author of Net Zero, Chris Skidmore, to undertake a ‘review’ of the policy agenda – asking greens to mark their own homework, in other words. The Sunak administration realised, at long last, that boiler and car bans were not going to play well with voters, and began attempting to water them down. But it was too late.

The true heir to Johnson’s green zeal is Ed Miliband. And what is the Secretary of State for Energy Security and Net Zero’s response to the hammer blow, if not coup de grâce for climate policies? Predictably, he has doubled down, insisting that “the transition is now unstoppable” and “90% of the world is now covered by Net Zero targets”. Yes Ed, but China’s “targets” don’t appear to exclude approving two new coal power plants every week. It’s “tough”, Miliband admits, but fret not, ye faithful, for “the role of UK leadership here is to do the right thing at home, because it’s the right thing for energy security”. The UK may be “only 1% of emissions”, but “the power of example really matters”. After five years under Ed, the UK may well be an example, but not one to follow.

When Trump last withdrew the USA from the Paris Agreement in 2017, the EU’s response, as reported by the FT, was to “forge” a “new alliance” with China. That is unlikely to be repeated, if for no other reason than that “alliance” resulted in China substantially increasing its emissions by multiples more than the EU’s reductions. And European green unity faces increased domestic pressures, in addition to a radically altered global political context. According to Euractiv, the European Peoples Party – the largest bloc in the EU Parliament, which includes von der Leyen herself – wants to renegotiate green policies, including freezing CO2 taxes and abandoning renewable energy targets.

At the 2024 COP29 meeting in Baku, Azerbaijan, a week after Trump’s re-election, a buoyant Ed Miliband declared that “Britain is back in the business of climate leadership”. But who are we leading? With governments representing half of the world’s economy and population signalling fading interest, and with Western governments and financial institutions falling away from the core of the climate policy agenda, Miliband seems to believe that it is still 2009. As those other countries abandon Net Zero policies and pull ahead economically, the pain of Britain sinking into a post-industrial abyss will become too much even for Miliband with his characteristic intransigence to ignore. The only question that remains, therefore, is for how much longer Keir Starmer will allow Miliband to remain in office?